We’ve nearly finished with the desert section of California. While we’re all looking forward to the Sierras, the desert has been its own kind of beautiful to us Michiganders. There’s been so much wildlife; herptiles (reptiles & amphibians), birds, mammals and insects. While they’re harder to capture than plants, some (mostly reptiles) have been quite photogenic.

From a distance they blend in incredibly well and don’t seem to be afraid of trekking poles. However they do seem to fear me picking them up and promptly scatter.

Western fence lizards (Sceloporus occidentalis) are more common and much easier to spot.

More common and skiddish than the fence lizards are common side blotched lizards (Uta stansburiana). Males and females of this species exhibit different color morphs, each indicative of their mating and reproductive strategies.

Blue throated males do not produce as much testosterone as their orange counterpart, making them smaller and able to form strong pair bonds. These males have smaller territories and are more guarded of their females.

Yellow throated males are the smallest of the three morphs and mimic female coloration. This allows them to approach and mate with females while orange throated males are distracted.

At Eagle Rock I came across a more rare lizard species, the granite spiny lizard (Sceloporus orcutti). They can be found basking on rock outcrops in their small range of Southern California.

On a sunny day their scales appear metallic and feature a wide range of colors. Though darker phase males and females may appear more drab.

These lizards are apprehensive of other species (especially humans) and are very skilled climbers.

These prehistoric looking alligator lizards (Elgaria multicarinata) have been much less common and generally don’t stick around long enough for pictures. There are three different subspecies with blue, yellow and red color morphs.

Our first real animal encounter was a rosy boa (Lichanura trivirgata) that this gentleman ahead of us found.

He said they’re rare sightings and seemed to know what he was talking about. A couple days later we came across some other hikers stopped for a snake they weren’t sure about. I was excited to inform them it was another rosy boa!

Somewhere around mile 200 I encountered my first rattlesnake. We were equally startled by each other as I rushed past. I didn’t expect the rattle to sound like it does in movies, that almost fake sounding baby’s rattle.

About a week later we encountered this rattler coiled up under a shrub right next to the trail.

While we were able to easily skirt the trail around it, this was probably the most terrifying one we came across. At no point did it rattle, just sat there coiled in striking position.

That same day we saw this rattler crossing a dirt road below us.

And then on our final push into Tehachapi they nearly missed another gopher snake.

And finally, this scene was hard to miss…

While I haven’t gotten any amphibian pictures, there are more of them out here than I anticipated. There are 8 species of salamander is Southern California, but we have not been so lucky to see any. Around wet campsites we’ve heard frogs calling and seen toads hopping about.

On our way to Whitewater Preserve at mile 218 I caught a hawk soaring through the valley.

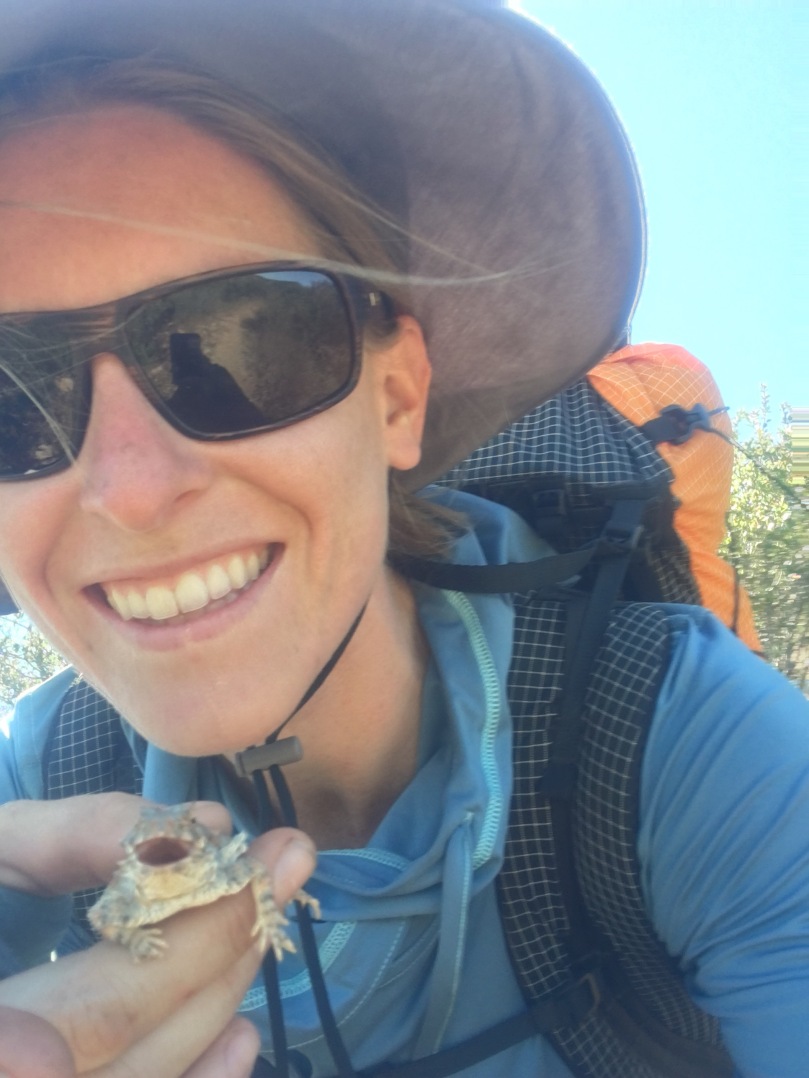

Then I rounded the corner and was surprised by said hawk.

So I obviously took a selfie.

Here’s a short list of birds I’ve been able to identify:

- American crow (and lots of them)

- Mountain bluebird

- American goldfinch

- Tree swallow

- California trasher

- California scrub-jay

- Stellar’s jay

- Pinyon jay

- Northern harrier

- American kestrel

- Red tailed hawk

- Cooper’s hawk

- Several humming bird spp.

- Several woodpecker spp.

- Several swallow spp.

Mammals have also been difficult to photograph, but there’s been plenty evidence of them in the form of scat.

There have been a good deal of mice. Luckily none of them have tried to get into our food. When we set up camp after finishing our night hike of the LA aqua duct I must have seen a dozen kangaroo mice with my headlamp.

There have also been pretty things like butterflies. I’ve seen numerous monarchs, swallowtails and California sister butterflies, but most are skilled in evading my pictures.

My initial thought was that it was a flightless bee. Further research led me to a velvet ant. Which isn’t an ant at all, but a wasp. The females, unlike males, don’t have wings, but make up for that lack of defense with a painful sting.

Their larvae are parasitic, meaning they feed on a host. For the thistle down velvet ant, those hosts are sand wasps. The female simply drops her eggs in the nest of a sand wasp and the velvet ant larvae consumes the sand wasp larvae before emerging.

Another parasitic insect species we’ve frequently come across are great golden digger wasps (Shpex ichneumoneus).

This was an unexpected and very exciting moment to catch. This female digger wasp creates many small tunnels as she prepares to lay eggs. When ready she stalks, stings and paralyzes her prey (the caterpillar in this video). Once immobile, she clasps onto the prey with her mandibles (mouth parts) and flys/drags them back to a tunnel. After inspecting the tunnel, she drags the prey in, lays an egg on it, exits and covers the tunnel. The wasp larvae then feed on the immobilized, living prey before gaining the strength to emerge.

We’ve seen so much cool stuff so far and can’t wait to see what the Sierras have in store for us.