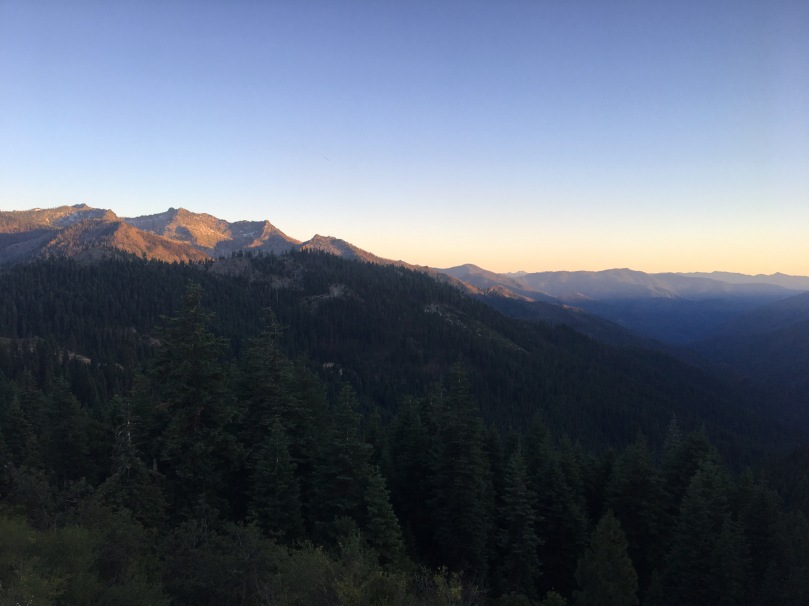

Northern California exceeded my expectations in so many ways. The lush coniferous forests are home to an incredible number of flowers, some more familiar than others.

Often seen as an ornamental, Washington or Shasta lilies (Lilium washingtonianum) are easily recognized peaking out a hillside.

This wonderfully fragrant lily is named after Martha Washington, it is not found in the state. We started seeing them around the time we saw views of Mount Shasta. I’d guess that explains the second common name, but can’t say that with certainty.

Shasta lilies are found in montane forests and meadows, habitat they share with the Columbian lily (Lilium columbianum).

A less recognizable species of lily we came across was Kelley’s lily (Lilium kelleyanum). This species is distinct by the drooping tips of its whorled leaves and long red anthers.

Kelley’s lily is endemic to California where they grow primarily in wetlands and are pollinated by swallowtail butterflies.

Another member of the lily family endemic to California is the Sierra Nevada fawnlily (Erythronium purpurascens).

These small perennials grow at high elevations and bloom early in the season after snow melt. Also known as purple fawnlily becuase the tepals turn purple with age.

What are tepals you ask? Before we can really talk about tepals, it’s important to know that one of the main characteristics of the lily family is that their flower parts are arranged in threes. While it may look like the previous species of lily have six petals, they have three petals and three sepals. When these parts are indistiguahable they’re referred to as tepals.

This naked mariposa lily (Calochortus nudus) provides a good example of distingushed petals and sepals. The petals being the large white rounded parts and the sepals being the pointed white parts in between.

This lily is named becuase of the lack of hairs on the petals that many other species of the genus have. It is native to mountains of California and southwestern Oregon where grows in wet areas.

Tolmie’s mariposa lily is a good comparison to show hairs on the petals as is common to the genus.

Like many Chalochortus species, the bulb is edible and can be consumed raw or boiled. Not only were various species of these bulbs harvested by Native Americans, Mormon settlers ate them during their first couple years of settlement in The Great Salt Lake Valley after crop failure.

Less readily recognized as a lily was Queen’s cup (Clintonia uniflora). Native to mountains of the northwest, this small flower can be found in the understory of coniferous forests.

In late summer a single small blue berry develops. These berries are a favorite of ruffed grouse, but are poisonous to humans.

These long stretches of coniferous forest were home to numerous species of the Heath (Ericaceae) family. Members of the heath family have alternating evergreen leaves and red or white bell shaped flowers with 4 or 5 parts. Plants in this family tend to grow in acidic or infertile soil which gives way to some cool adaptations.

Pipsissewa or Prince’s pine (Chimaphilia umbellata) grows throughout the US in cool, moist forests. This ground cover was traditionally used by Native Americans as a medicinal tea.

Today it is commercially harvested in the Northwest where their leaves, stems and rhizomes (roots) are used for cola and root beer flavoring.

While pipsissewa have green leaves, they do not receive a significant portion of their nutrients from photosynthesis. Rather they are partial myco-heterotroph, gaining nutrients from parasitism of fungi in the soil.

Species of the genus Pyrola, like this whiteveined wintergreen (Pyrola picta) are also partial myco-heterotrophs.

There’s a bit of controversy in the botanical world regarding the number of Pyrola species found in the US due to the following leafless member.

Whiteveined wintergreen has greenish-white flowers, while bog wintergreen has pink. This leafless variety tends to have both, therefore some consider it an entirely seperate species. I bet you can guess what’s it’s called…leafless wintergreen (Pyrola aphylla).

Leafless wintergreen is a true mycotroph, obtaining all of its nutrients from mycorrhizae, the fungus conifers use to procure additional moisture and nutrients. Botanists are working to sequence DNA and isatopes in order to determine if it is truly its own species.

Another fully mycotrophic member of the Heath family seen frequently after snow melt is snow plant (Sarcodes sanguinea).

Although it is fairly uncommon, this plant is easy to spot growing out of forest litter. Native to California, Oregon and Nevada, they can be found in colonies near the base of conifers.

Over lapping range in the northern Sierra Nevada with snow plant is pinedrops (Pterospora andromedea).

I’d hoped since first seeing California groundcone (Boschniakia strobilacea) in my wildflower app that we would come across it. I can’t tell you how many upright pine cones I was sure were this parastite before finally stumbling upon one.

California groundcone is a member of the broomrape family. Like it’s relative, Indian paintbrush, it has haustoria instead of roots. These root-like organs penetrate the roots of madrone (Arbutus spp.) trees and manzanita (Arctostaphylos spp.) shrubs.

One of the more common parasitic plants in these stretches of forest were Pacific coralroot (Corallorhiza mertensiana). As you can see from the photos, this species of orchid can be variable in color.

Once thought to be a sub species of spotted coralroot (Corallorrhiza maculata), it was given species rank in 1997. Pacific coralroot only parasitize mutually exclusive species of fungi in the Russulaceae family and will never share fungus with spotted coralroot.

Much less colorful, but equally as mycotropic is the snow orchid (Cephalanthera austiniae).

This species of orchid is unique as it is the only species of its genus native to the Western Hemisphere. It is also the only species of its genus that is fully mycotropic.

Although the slender-spire orchid (Piperia unalascensis) is not a mycotroph like the previous few, it can be found in the same woodland habitats.

Native to much of western North America, parts of eastern Canada and the Great Lakes. The flowers become fragrant in the evening releasing a musky, soapy, honeylike scent.

A widely spread member of the sunflower family, broadleaf arnica (Arnica latifolia) can be easily distinguished by its oppositely arranged, heart-shaped, toothed leaves.

Broadleaf arnica is found in montane forest and meadows throughout the western United States.

Another common flower that barely waits for snow to melt is western spring beauty (Claytonia lanceolata).

Also known as Indian potato, due to the cooked stems resemblance. This member of the purslane family is commonly found in forests and wetlands.

The most widespread forest plant we’ve come across is plumed Solomon’s seal (Maianthemum racemosum). This false Solomon’s seal can be found in every state but Hawaii.

Young shoots can be simmered and are said to be reminiscent of asparagus. Like many plants, onceflowered and seeded it becomes too bitter and fiberous. The Ojibwa soaked them overnight in lye to remove the bitterness and strong laxative qualities.

A new wildflower for me, California harebell (Asyneuma prenanthoides) is tall and slender with tiny purple flowers.

With more limited distribution from northwest California to southwest Oregon, California harebell is found in coniferous forests.

Another coniferous forest dweller native to the west coast is western white anemone (Anemone deltoidea).

This anemone is another example of a flower with tepals, five to seven in this case.

Bigelow’s sneezeweed (Helenium bigelovii) might look familiar as there are numerous cultivars raised for landscaping.

A single plant can produce up to 20 flower heads, likely part of its horticultural allure. This member of the sunflower family is found in moist meadows and marshes of California and Oregon.

Primarily a wetland species, white bog orchid (Platanthera dilatata) is widely distributed throughout Canada and the United States.

The stem can bear up to 65 fragrant flowers that are pollinated by skippers and owlet moths.

One of my personal favorites, alpine shooting star (Primula tetrandra) is a member of the primrose family found in wet montane environments.

All species of shooting star require buzz pollination, or sonication. This is a technique that some bumble bees employ in order to release pollen firmly held by the anthers. It is done by grabbing onto a flower and rapidly moving their flight muscles. This causes the flower and anther to vibrate, therefore dislodging pollen.

To my knowledge, the only carnivorous plant we’ve come across is California pitcher plant (Darlingtonia californica). Pitcher plants are really fascinating, but I’ll try and keep this brief…

Native to northern California and southern Oregon, this species of pitcher plant can be found in bogs or seeps of cold running water. Due to the lack of nutrients in these soils, pitcher plants supplement nitrogen through carnivory.

This species of pitcher plant is unique due to the placement of its exit hole and the numerous false exits as can be seen in the bottom left photo. The top right photo shows the flower, it is oddly shaped and complex which is indicative of a close pollinator relationship. However at this time no pollinators have been witnessed or identified.

A little less recognizable flower found in many similar moist montane environments is white rushlily (Hastingsia alba).

Native to Northern California and southern Oregon, this species was once considered part of the lily family due to the black coated bulb it grows from. It has since been classified as part of the asparagus family along side desert agave (Agave deserti) and Joshua tree (Yucca brevifolia).

Common to moist montane meadows of the west is California corn lily (Veratrum californicum).

Also native to the mountains of the west is subalpine fleabane (Erigeron glacialis).

In the Sierra Nevadas it can be found in moist, mixed conifer forests up to 11,200 ft in elevation. This, along with the next two species were found in very close proximity to each other on a rocky cold water seep.

Fivestamen miterwort (Pectiantia pentandra) is more restricted in elevation being found only between 5,000 and 8,300 feet in the Sierra Nevada.

Perhaps a more commonly recognized riparian flower is white marsh marigold (Caltha laptosepala).

So many plants we came across went unidentified or had pictures that didn’t do them justice. Lucky for me, some of them have been in southern Oregon.